HISTORY

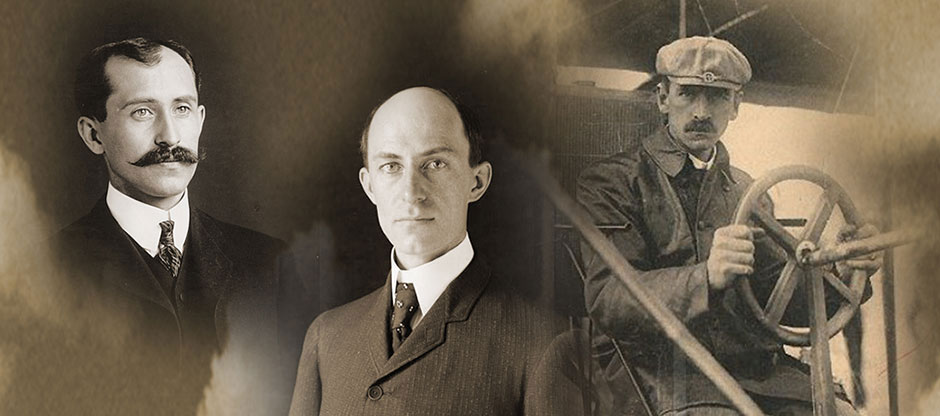

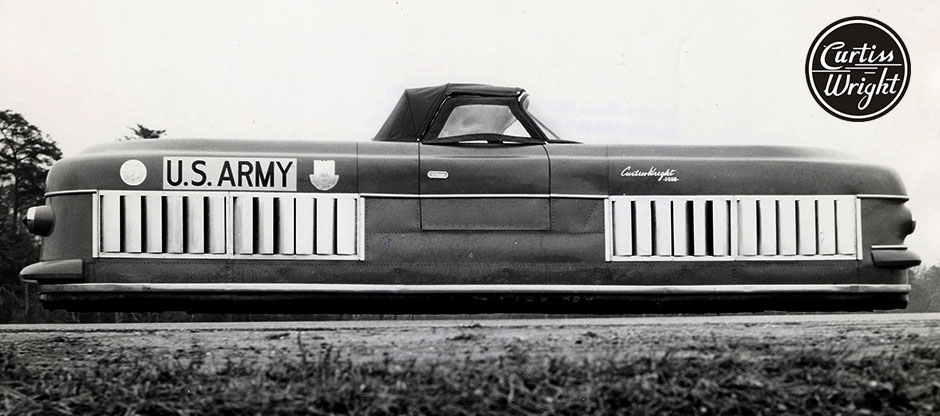

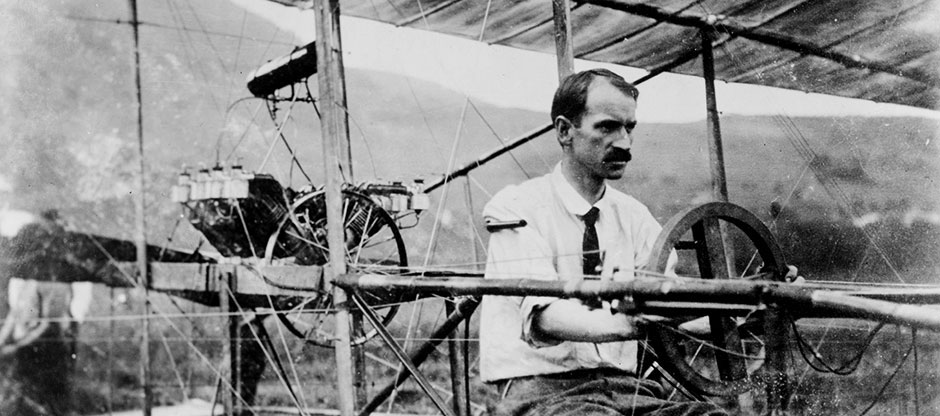

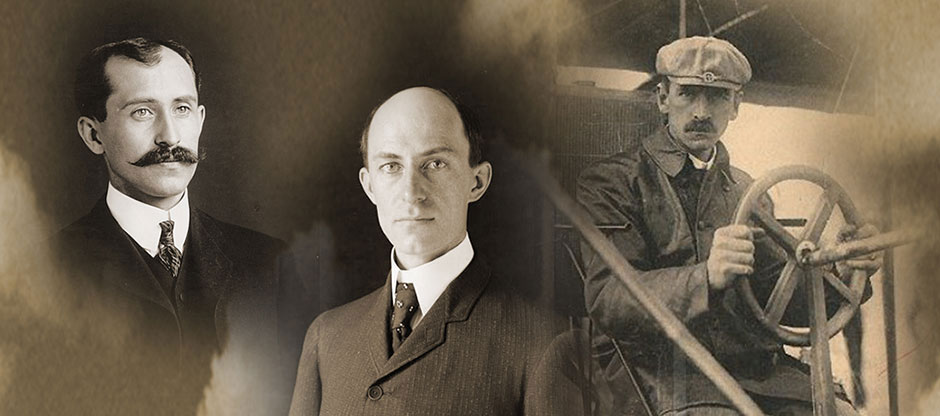

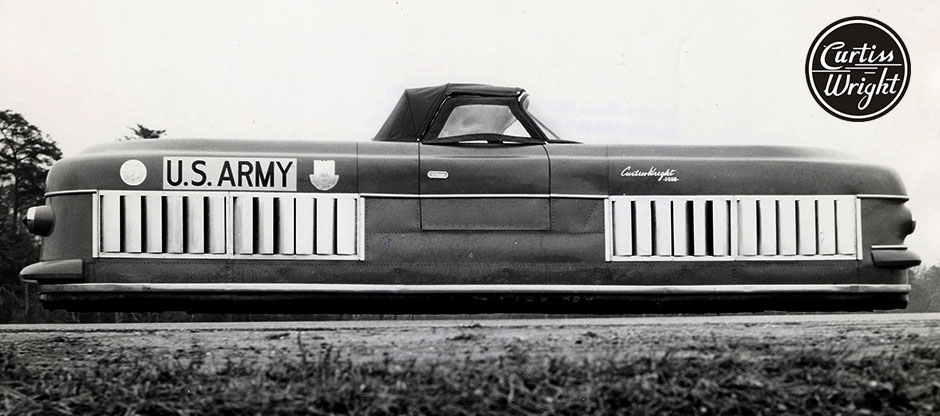

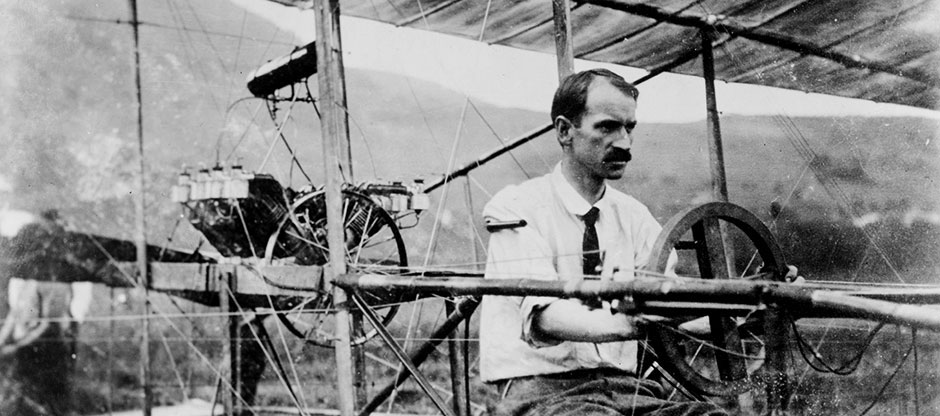

95 Years of Growth Curtiss-Wright Corporation has the most renowned legacy in the aerospace industry. In 1929, Curtiss-Wright was formed by the merger of companies founded by Glenn Curtiss, the father of naval aviation, and the Wright brothers, renowned for history’s first flight. These technological pioneers ushered in the era of aviation and their trailblazing spirit made history. Curtiss-Wright has changed dramatically over the past nine decades, and continues to transform itself to be at the forefront of the markets that we serve.

Today, Curtiss-Wright is a global, integrated market-facing business that remains a technology leader through this legacy of innovation. We maintain an extensive offering of critical products and services that were either developed internally or joined through strategic acquisitions. Our structure drives the focus upon our diversified end markets through three well-balanced segments – Aerospace & Industrial, Defense Electronics and Naval & Power – where we remain focused on advanced technologies for high performance platforms and critical applications. Furthermore, our technologies provide increased safety, reliability, and performance in the most demanding environments, serving numerous customers across a multitude of industries.

Diversity, commitment to excellence and dedication to the spirit of pioneering innovation continue to drive the employees of Curtiss-Wright.

[ 1903 - 1999 ] THE 20TH CENTURY

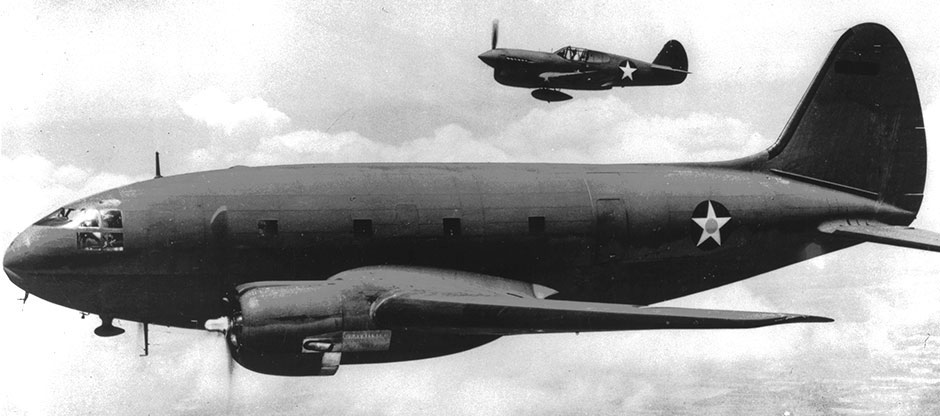

Our legacy of innovation has its roots in the earliest successes of the Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss. The eventual merger of Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Corporation with Wright Aeronautical Corporation in 1929, a few months before the start of the Great Depression, brought together 18 affiliated companies and 29 subsidiaries, which formally created the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. With total assets of more than $70 million and stock valued at $220 million, the company was immediately considered the world's most prodigious aviation concern.

CLICK TABS TO READ MORE ABOUT EACH DECADE

[ 2000 - 2011 ] THE START OF THE 21ST CENTURY

The first decade of the 21st century saw the transformation of Curtiss-Wright from less than $300 million in revenues to a global technology player with sales exceeding $2 billion. We achieved this through solid organic growth and the strategic acquisition of nearly 60 businesses, paired with a consistent focus on strategic investments and improved operational efficiency.

Where we were once a company highly dependent on the commercial aerospace market, we took actions to broaden our technology portfolio and the core markets in which we compete. In 2000, we began to diversify away from Commercial Aerospace and become less reliant on one market to drive our growth; during this time we branched out into Defense Electronics, such as sensors and embedded computing, and significantly expanded our energy markets, particularly within the commercial nuclear power and oil and gas industries.

In addition, the events of September 11, 2001, had a dramatic effect on the U.S. defense industry that accelerated the need for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance equipment and led to a steady increase in defense spending. Curtiss-Wright supported our armed forces through the development of advanced technology and proprietary products serving the naval, aerospace and ground defense markets.

Throughout the 2000 decade, we executed our diversification strategy, generating balanced growth across our various end markets along with a rapidly expanding global footprint. Diversification was a cornerstone of our overall strategy.

Even today, Curtiss-Wright remains focused on the acquisition of companies that bring industry leading technologies and capabilities, which are positioned for solid growth where we can further improve their operations and expand their profitability after joining Curtiss-Wright. We look for companies that can provide the right combination of balance to our market diversification, along with the ability to expand our breadth of technologies, products and services into both existing as well as high-growth or emerging markets.

Under the former strategy, the long-term goal was to achieve a 15% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in sales through a combination of strategic acquisitions supplemented by organic growth. Furthermore, our consistent focus on strategic investments and improved operational efficiency positioned us to grow our profits faster than sales which, in return, improved the competitiveness of our company for the long term. We also maintained a balanced capital structure, which enabled us to continue to expand our operations and actively pursue strategic acquisitions.

[ 2012 AND 2013 ] TRANSFORMATION

The transformation of Curtiss-Wright continued, as we acquired 7 businesses between the third quarter of 2012 and first quarter of 2013 that dramatically influenced our end market mix, addressable markets and product portfolio. The Company continued to employ its diversification and acquisition strategies that further strengthened our commercial end market offering, particularly in the general industrial market, and created a more balanced portfolio that positions Curtiss-Wright for continued success.

Those acquisitions follow our stated intention to further expand our sensor and controls offering while looking for opportunities to leverage our existing strengths and capabilities, to move up the chain in our oil and gas business, to add niche nuclear power generation companies with strong technological offerings, and move up the chain in our Surface Technologies business. We believe that these acquisitions accomplished all of the above, which provided an ample opportunity to continue to grow our business by further expanding our product offerings into adjacent markets and geographies.

[ 2014 TO PRESENT ] ONE CURTISS-WRIGHT

In 2014, we transitioned to a new segment structure under the “One Curtiss-Wright” vision, realigning our business to a market-facing, global integrated company. We are concentrating on growing steadily by leveraging the critical mass and powerful suite of capabilities we built over the past decade, while driving operational excellence and financial discipline to achieve top quartile performance as compared to our peer group. While we currently enjoy leading positions in several of our served key markets, our goal is to be #1 or #2 in all our key end markets, to be the trusted “go to” company in solving the most difficult engineering problems within specific specialties or solutions.

We continually focus on maintaining solid relationships with our customers, building on our competitive positions and creating market leadership through our technology investment. In this new structure, we will better utilize our scale while also providing for enhanced customer interaction. These strategies will continue to support our growth and generate margin expansion opportunities.

As part of that 2014 transition, we set and later achieved each of our five-year financial objectives: 3-5% organic sales growth, double-digit EPS growth, top quartile operating margins (14%+), greater than 12% Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and at least 110% free cash flow conversion. We paired these objectives with a focus on a balanced capital deployment strategy which included returns to shareholders (in the form of share repurchase and dividends), capital investments and acquisitions.

We will never sit still, and in 2021 we began the next phase of our evolution with our Pivot to Growth strategy, driven by a renewed drive for top line acceleration through both organic and inorganic sales growth, building on the strengths across our A&D and Commercial markets. We established new long-term targets for the three-year period ending in 2023: 5-10% Total Revenue Growth; Operating Income Growth > Revenue Growth; Top Quartile Margin Performance; >= 10% CAGR Adjusted EPS Growth; > 110% Free Cash Flow Conversion.

Top quartile performance metrics, combined with our disciplined capital deployment strategy, will serve to improve the competitiveness of Curtiss-Wright over the long term and significantly expand value for all of our stakeholders.